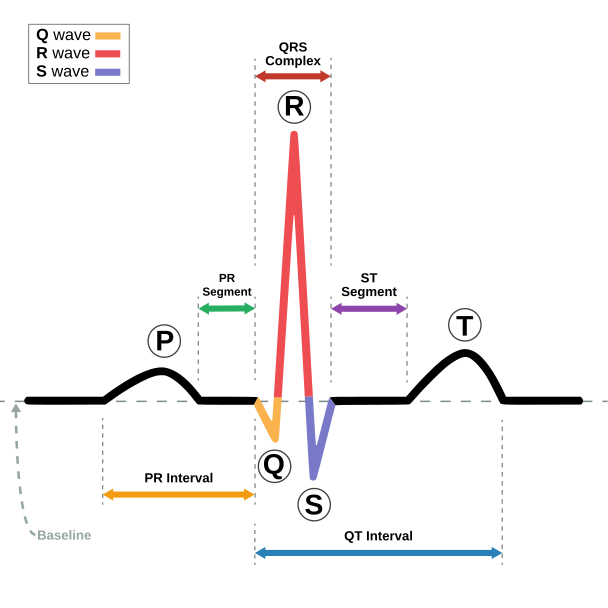

Remembering back to Anatomy and Physiology, this what one single heartbeat looks like on an ECG:

|

| From: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SinusRhythmLabels.svg |

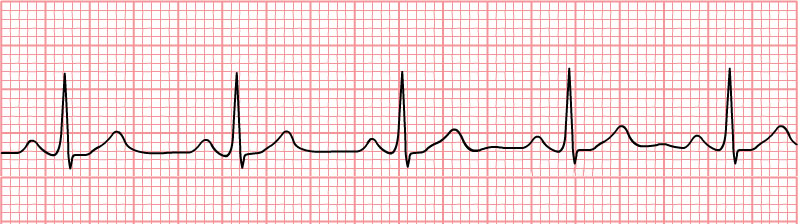

If that is a normal complex, then, a normal ECG looks like this:

|

From https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Normal_Sinus_Rhythm_Unlabeled.jpg

|

Note that the rhythm is regular: the distance between each of the p-waves is the same. On an abnormal ECG, the rhythm will be irregular: the beats will not all be the same distance from one another. Now you must determine if the the rhythm is regularly irregular or irregularly irregular. Huh? Let's look at that a bit more closely.

Regularly irregular means that there is a pattern to the irregularity. For instance, two beats are the same distance apart, but then the third one is spaced further. Then that pattern repeats: short, short, long, short, short, long.

Sinus arrhythmia (the heartbeat speeds up during inspiration) is a form of a regularly irregular heartbeat. Despite the fact that this is an arrhythmia, remember that it can be normal in dogs (but not cats!)

Irregularly irregular is when there is no pattern to the irregularity. This may show as differences in distance between waves, missing waves or 'extra' waves. Premature Ventricular Contractions (PVCs) are an example of an irregularly irregular rhythm. (Note that the UPenn website in the two previous links is an excellent resource for small animal cardiology.)

Since in practice we don't always have patients attached to an ECG for routine procedures, how will you know if they have an arrhythmia? When you auscultate the heart, it is important to not only count the rate, but note if the rate is regular. If it is irregular, determine if the irregularity is regular or irregular. While auscultating, watch the patient breathe. Does the rate change with inspiration? Palpate the pulse while auscultating; is there a pulse for each heartbeat? With practice, you will be able to hear irregularities while listening to the Doppler as well. If you are hearing dropped/missing beats, the irregularity of rhythm is not associated with respiration, or you are not feeling a pulse with each heart beat, get that patient hooked up to an ECG!

So, what types of arrhythmia are you most likely to see? This article outlines the five most common arrythmias seen in dogs and cats. Out of those five, from my experience, sinus arrhythmia, premature beats and atrioventricular (AV) block are those that are most commonly seen in general practice. You will note in the article that the captions of the AV block and premature beats state that the arrhythmia was auscultated: your ears are often the best tool for recognizing a problem! It is so important that we take the time to listen, not just count a quick heart beat, especially prior to an anesthetic. It takes less than 5 minutes to get a patient hooked up to an ECG and get a reading and it is definitely worth the time. Even if it is normal, the more you see, the easier it is to recognize an abnormal tracing.